The Pharaoh of Many Colours: An Egyptian’s Unsolicited Take on Afrocentrism

Living in culturally pluralistic societies and sharing the land with people who look and behave differently from us make us question our identity: Who am I? Where do I come from? What do I believe in? How do others see me vs. how do I see myself? We try to connect with our roots—or ancestors if you please. We seek solid ground on earth and loving saints in Heaven to intercede for us. For we aren’t a bunch of disconnected individuals as much as this modern world desperately tries to make us believe; we are a community and belong to a greater whole. And the sense of alienation this current world brings us is all but a good reason to find and reconnect with our extended and dispersed family.

Some people believe it’s easy to trace back their roots without a trace of doubt. Some claim they are a pure breed, a hundred percent of something, whatever that thing is. I’m hundred percent black; hundred percent white; hundred percent royal blood; a direct descendant of Jesus or Muhammad PBUH—even though with all the cultural cross-pollination and the mixing of bloodlines between different ethnic groups, it’s almost impossible to claim the purity of anything. For others, it’s even more challenging to track down their origins either because of a tragic historical event that took place at a point in time and disconnected people from their communities and homeland—like the Atlantic slave trade—or because of the unique experience of living in multicultural societies at the centre of extensive migratory trajectories or along trade routes or seaports. North Africans just happen to be some of those people that many of the world’s civilisations came together and made love to conceive. They come in all shades of colour and embody the beauty yet the perils of carrying an intersectional identity.

We saw it happen in the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar when Morocco made history with its mindblowing performance and became the first African and Arab nation to ever reach a semi-final at the world cup. All over social media, fans were celebrating frantically—those who considered it an African win celebrated alongside those who viewed it as an Arab one. But shortly after, questions started popping up on whether Morocco was African or Arab, or both—or neither. An image of Morocco’s goalkeeper, Munir Mohamedi, celebrating their win against Spain with an Amazigh flag instead of a Moroccan one around his waist sparked controversy among Arab fans all over the Arab world who were reminded that the majority of Moroccans consider themselves as Amazigh first and foremost. African fans were also disappointed when a few Moroccan football players, including Sofaine Boufal, failed to acknowledge Africa after their historic win over Portugal. Boufal was quoted as thanking all Moroccans, all Arabs, and all Muslims all over the world, but not Africans. He later apologised for not mentioning the African fans on his Instagram.

The recent fiasco in Tunisia is another example of how trying to force a single narrative of a nation’s identity could go wrong. In February 2023, the Tunisian president, Kais Saied, made offensive remarks that revealed—to say the least—the Afrophobic sentiments that North Africa has been grappling with for decades after the revolutionary fire of the Pan-African decolonial movement that spread throughout the continent in the sixties had slowly fizzled out. Saied claimed that sub-Saharan African migrants in Tunisia are part of a conspiracy to change the demographic composition of his country, which is predominantly Arab-Muslim. The ripple effect of his remarks was devastating and violent. It harmed not only the black African migrants—who fled to their embassies en masse to seek repatriation in fear for their lives—but many black Tunisians who were looked at suspiciously as outsiders simply because some thought you couldn’t be a black person and a Tunisian and an Arab and a Muslim all at the same time.

These remarks and many similar incidents echo the identity crisis that North African countries have been cursed with, including my home country Egypt—or Kemet, as some Afrocentrists prefer to call it. You won’t get a straight answer on how we identify ourselves; it depends on who you’re talking with. Even the West hasn’t decided on whether to classify us as the Middle East or North Africa or an Arab state or poor, just poor—as long as they distinguish us from sub-Saharan Africa for purely geopolitical and racial reasons. And the rest of the African continent isn’t any different. Some call us the descendants of colonisers and not real black Africans, yet some regard us as a showcase of the rich diversity of the motherland, for without North Africa, Africa won’t be whole.

And nationally, it depends on who governs us and their political agenda. During Nasser, Egypt was a Pan-African, Pan-Arab, Pan-everything country, provided it kept the British at arm’s length. Despite his black Nubian roots, Sadat had a different agenda and identified Egyptian nationalism as the primary influence behind his policies, even if it meant shaking hands with Menachem Begin, the Israeli prime minister, in 1977. Fast forward to 2013, when the Muslim Brotherhood, represented by Morsi, took over and declared Egypt an Islamic state. We’ve seen it all, really. Yet, we still fall into the trap of a single story—every single time. We still think that we are either this or that; we can’t be both; we can’t be everything all at once.

“We still think that we are either this or that; we can’t be both; we can’t be everything all at once.”

Earlier this year, Kevin Hart was quoted (or misquoted–still a mystery!) to have tweeted: We must teach our children the true history of Black Africans when they were kings in Egypt and not just the era of slavery that is cemented by education in America. Do you remember the time when we were kings?

As much as the Afrocentrist social media platforms circulated and celebrated this tweet, it was as if Kevin Hart dropped a nuclear bomb on many Egyptians, especially those who don’t identify as black. The angry and vindictive reactions to this tweet were mainly confined to Facebook groups with names that included a combination of against Afrocentrism, nationalist Egyptians, nationalist revival, Say No to Afrocentrism; except for that one action that manifested in real life, cancelling Hart’s first performance in Egypt last February, with the production company releasing a statement and attributing the cancellation to logistical reasons without giving further explanation.

Photo: Shreyas Nair

Do I think ancient Egyptians were black? That’s not the purpose of this essay, or maybe it is. I’ll figure that out later. But it’s really an essay about identity and how it’s mostly a social construct that changes with the change of place and time and so many other factors.

I have a small story to tell about my own identity.

Back in 2011, I moved to Washington, D.C., for a one-year study program, leaving behind a budding revolution in the streets of Cairo—an Arab Spring in the making. I landed at Dulles Airport wearing my Egyptian identity on my sleeve. I was so damn proud of who I was back then and couldn’t wait to share with the whole world what we did back there at Tahrir Square: a bunch of young people overthrowing the tyrant and reshaping the future of the country with their own bare hands. This is the version of the story that the twenty-five-year-old me believed and narrated through various American news platforms, including HuffPost and C-SPAN. I identified myself as a Coptic Egyptian woman everywhere I went, and the first question I would get was, “What is a Copt? Is it a religion? An ethnicity?” And without much thinking, I would declare with a pharaoh-like pride that Copts are an ethnoreligious group who were believed to be the descendants of ancient Egyptians, a pure breed that fought through and survived the invasions of Ptolemies, then the Romans, then the Arabs, then the Ottomans and the list goes on. “So, it’s not a religion? I thought Copts were Christians,” someone would say. And this is when I’d delve into the religious realm and give a quick rundown of the different religions brought by colonisers after shifting from a complex pantheon of gods to monotheism. Back then, I thought I knew who I was as much as I knew who I wasn’t. Back then, I wasn’t an Arab. Now, after all these years, I take pride in my Coptic-African-Arab intersectional identity. I was confident of my position in the world and carried this knowledge with me to the United States—until this confidence was shaken to the core during my first few months in D.C.

In the first couple of months, I did a work placement at a public policy institute in the heart of the National Mall. My coworkers were mostly white—and Republicans—and I instantly felt out of place. In my first week, some of them were curious about my Arab Spring experience and my identity as a young Coptic woman because of all the media buzz. The CEO decided to organise a panel discussion for other policymakers and politicians and invited two Egyptian fellows and me to speak about our experience. He even wrote an op-ed about the revolution and the power of youth civic engagement. Even though I was grateful to be given the platform to express myself, something was off. The same coworkers who were initially curious to hear my story wouldn’t even say good morning when we bumped into each other in the elevator, nor did they ask me to join them during lunch breaks. I was clearly an outsider, and outside being a spectacle, I didn’t really exist. None of my Coptic pure-breed Egyptian Arab-speaking identity mattered at this point—I just wasn’t white. Period.

Four months into my fellowship and I was fed up. I wasn’t learning much apart from the cultural exposure, and the feelings of alienation and worthlessness seeped deeper into my soul. My mind was still in Egypt, and watching the devastating news of the army killing the protestors in the streets made me question what the hell I was doing back in the U.S. I decided to speak with the CEO and share how I felt out of place, that I originally applied for this fellowship because I wanted to do some real community work instead of sitting in an office all day writing papers. He looked at me with raised eyebrows, then finally said, “I could tell from day one that you felt disoriented but thought you just needed time. Why don’t you go back to Egypt for a short visit, and when you return, I’ll arrange for you to continue your placement in a community organisation in the Anacostia.”

Those who live in or visit D.C. probably know that Anacostia is a predominantly black neighbourhood in the southeast of the city, notorious for its high violent crime rate and public housing apartment complexes. The first thing I was told by the fellowship administration during the orientation week was to avoid this part of the city. “It is not safe,” they said. So, when I learned from the CEO that I’d be placed in an organisation in the Anacostia, I seriously thought he just wanted to get rid of me. And looking back, I thank Heaven that he wanted me gone, for my experience in the Anacostia was transformative and life-changing.

The Anacostia community centre had only one white staff member; everyone else was black. I was still in D.C., probably a few blocks from the National Mall, but I was immersed in a completely different culture, as if I had left Mars and gone to Saturn. My non-whiteness no longer tormented me. I was finally an African among other Africans, but are they Africans? They are Americans, after all, African Americans. What does this really mean? My Africaness was foreign to them as much as their African Americaness was foreign to me. (Mind you, this was the first time I had a proper encounter with an African American, and many of my coworkers didn’t know much about Africa except for the undignified narrative pushed by the U.S. media.) So, we took our time over the eight months I spent there to know each other, and by know, I mean know—like digging deeper underneath the stereotypes and the hearsay and the fear of the unknown. Unlike my white coworkers back at the policy institute, my new coworkers cared about knowing me as a person more than my political and public life achievements, which was what I yearned for back then, being away from home and family.

But I still had to explain my identity, and words like Copt and Egyptian weren’t familiar to them. Are you mixed? Are you an Ethiopian? Where is Egypt? Are you black? This is what mattered where I was. If I have black blood in me, then I’m family. This is what the people surrounding me needed to know. And I also needed to know because I didn’t—I didn’t know how to answer when someone asked me if I was black. Clearly, my skin was light brown (if that’s even the right shade), but the word black meant something more profound than skin colour. You look like you have black blood in you, another would say. And I had no idea what that meant, but I started to believe it myself. I’m definitely African, I’m definitely pan-African, and therefore I’m black.

I later met a Rastafarian during my bus ride back to my residence in Columbia Heights, and when I told him I was Egyptian, he gave me a crash course on Kemet and ancient black Egyptians. “Don’t let the white man fool you. They are trying to whitewash everything, including our history, our ancestors.” Our? So, you also consider ancient Egyptians your ancestors. How? There wasn’t enough time to continue the conversation. We exchanged emails but never got in touch. And I completely forgot about this encounter.

“Clearly, my skin was light brown (if that’s even the right shade), but the word black meant something more profound than skin colour.”

Now, twelve years later, and with social media erupting with news about Kevin Hart’s event cancellation and the Netflix black Cleopatra show controversy, I came across Afrocentric Facebook groups and Instagram posts claiming that all modern Egyptians are the descendants of colonisers and have nothing to do with ancient Egyptians. I was stunned. This just didn’t make sense, as there is no documentation of mass extermination—or mass exodus— in the history of Egypt, as far as I know. Yes, colonisers and invaders came and went as in any other country on the continent, and bloodlines mixed, but to make this statement is outright appalling and nonsensical. Imagine someone telling you that your ancestors aren’t really your ancestors, that you are the descendant of thieves and colonisers. Even if you don’t believe them, even if they have no evidence, it would still hurt like hell.

And this is when I remembered the Rastafarian and the bus ride and our long conversation. He never said I was the descendant of colonisers. He said “our history”. I wish we had continued that conversation.

Every day now, I read through dozens of posts on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter from both the Afrocentric and anti-Afrocentrism Egyptian sides, but I fail to find anything of substance in these posts. Both exchange racial slurs and accusations of either whitewashing or blackwashing ancient Egyptians, accompanied by edited photos and complex genetic codes to support their arguments. And between this diarrhoea of pseudohistory, armchair research, and racial supremacy, I couldn’t find any solid information to answer the questions burning inside me.

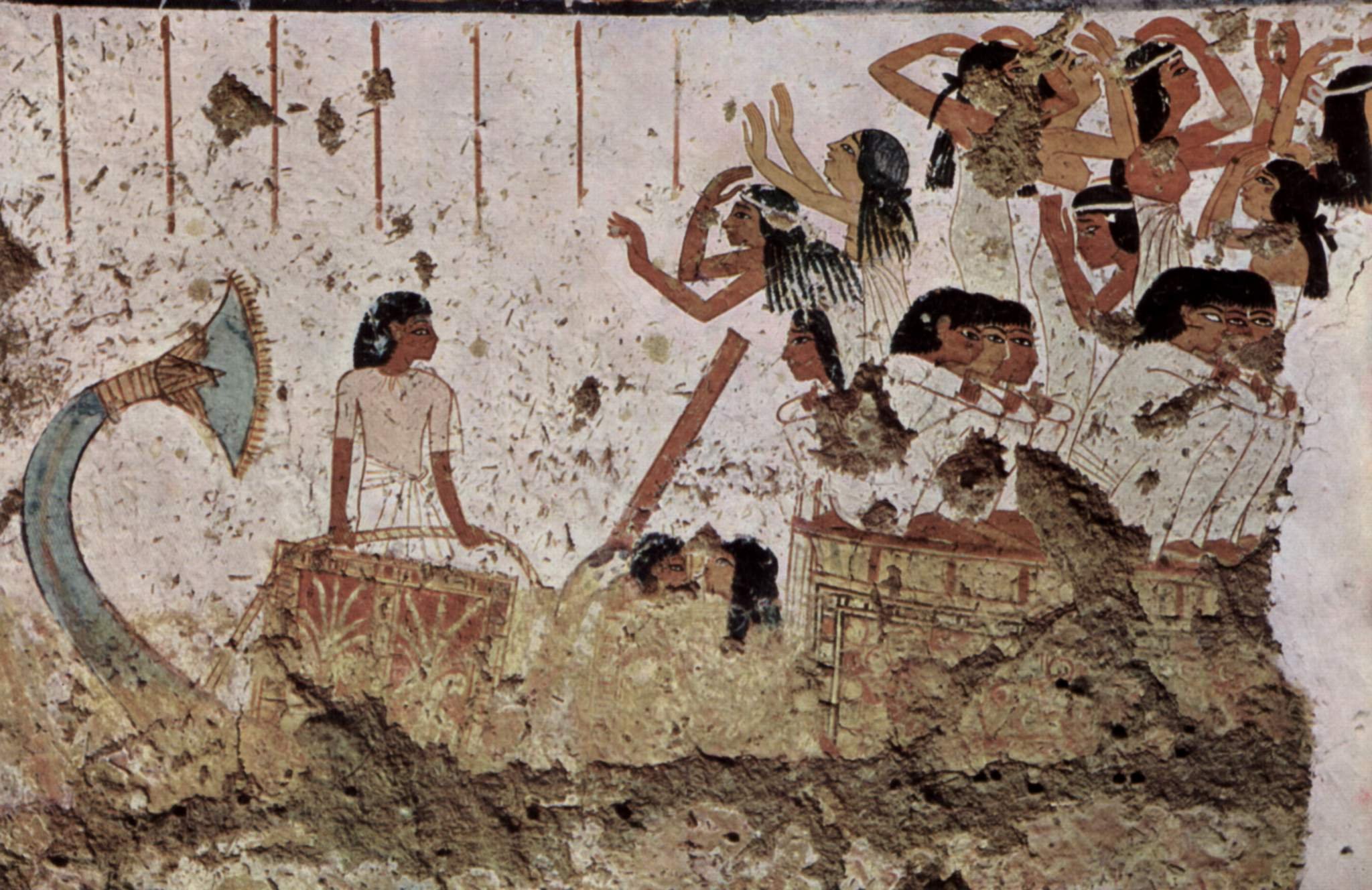

I went back to the photos I had taken of temples and ancient tombs that I had saved on a hard drive and started gazing at the mural paintings. Many of the featured gods and goddesses weren’t even humans. (So unless you’re a jackal or a crocodile, you can’t really claim ancestry.) Then I noticed that these murals mostly depicted kings and queens and priests. Commoners weren’t part of the narrative and weren’t important enough to make it to these royal paintings—unless they served royals or worked on the farms. I needed to look at these murals from the viewpoint of ancient Egyptians back in the day. These murals weren’t painted to inform or educate future generations about how black or white the royals were—they weren’t even meant to be seen by commoners—but were mainly part of sacred and religious rituals.

But did they look black? They looked reddish brown to me. Some were fairer than others, some darker than others. Some murals even lost their colour. Mostly figures with black wigs and dark eyes lined with prominent kohl. Their features looked similar—yet different in a sense—to many modern Egyptians, Sudanese, Eritreans, Ethiopians, Somalis, and other Northeastern Africans. But this is my personal bias speaking, and someone else might look at the exact same murals and have a different impression.

That’s it! That’s the most of what I could get out of these paintings. Did it answer any of my questions? Hell, no! All I was trying to do was to force thirty-one ancient dynasties that spanned across three thousand years into one single group or a shade of skin to prove a point—that I am a legitimate heir.

I am still left with questions . . .

What is black?

Are mixed Africans black?

Is the definition of black in the U.S. the same as black in the continent of Africa?

Do African Americans and Africans share the same understanding and experience of being black?

Where do Copts stand in the black non-black spectrum?

Can you be black and Arab at the same time?

What is Afrocentrism to African Americans vs. to Africans living in Africa?

Who am I?

Until recently, I thought of myself as Pan-African. I dreamt of Africans living on the continent or in the diaspora—with all their shades and colours and ethnocultural backgrounds—coming together as friends, as brothers and sisters, and trying to find solutions to issues eating up the continent from the inside out, like climate change, corrupt governments, racism and colourism, neocolonial powers still sucking our blood, failing economies. Isn’t that why the Organisation of African Unity and later the African Union was formed, to encourage economic and political integration among African countries and eradicate colonialism and neo-colonialism in the continent? What happened to the collective African identity? Shouldn’t Afrocentrism unite Africans with all their shades and backgrounds instead of further segregating them?

Great thinkers like the Afro-Caribbean political philosopher Frantz Fanon foresaw the problematic dichotomy between Africa, north of the Sahara and Africa, south of the Sahara and wrote about it in his masterpiece, “The Wretched of the Earth”:

Colonialism shamelessly pulls all these strings, only too content to see the Africans, who were once in league against it, tear at each other’s throats. . . . Africa is divided into a white region and a black region. The substitute names of sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa are unable to mask this latent racism. . . .There are some places where black minorities are confined in semi-slavery, which justifies the caution, even distrust, that the countries of Black Africa manifest toward the countries of White Africa. It is not unusual for a citizen of Black Africa walking in a city of White Africa to hear children call him “nigger" or to find the authorities speaking to him in pidgin. . . . Likewise, in certain newly independent states of Black Africa, members of parliament, even government ministers, solemnly declare that the danger lies not in a reoccupation of their country by a colonial power but a possible invasion by “Arab vandals from the north.”

In this section, Fanon was talking specifically about the young national bourgeoisie who took control of African governments after decolonisation and employed racism to achieve power in the name of a narrow-minded nationalism at the expense of African unity. Different times and different ideologies, yet the same dilemma confronts our continent nowadays.

I started looking up references about Afrocentrism beyond the messy world of social media, and I came across an insightful article by William Cobb Jr. titled “Out of Africa: The Dilemmas of Afrocentricity”. This article and other readings made me realise that Afrocentrism is much more than fighting over the birthright of the ancient Egyptian civilisation. It’s about claiming back the black history that was consistently whitewashed throughout the years, taking pride in African civilisations that enriched our current world, and debunking the myth that Greece and Rome are the cradles of civilisations. Yet, the dilemma of Afrocentricity, according to Cobb, is the challenge of instituting a valid and affirming identity without lapsing into essentialist theories of race superiority. I would add to that instituting an affirming and inclusive African identity that encompasses all ethnocultures, shades, and colours that make up the continent of Africa. Africa isn’t monochrome as some Afrocentrists claim it to be, and as long as we depict it as such, the dream of One Africa is a lost cause.

Are all Africans black? And I’m not talking about the white European settlers.

I’m talking about Egyptians, Sudanese, Moroccans, Libyans, Tunisians, Algerians, Mauritanians, Malagasy.

What about Ethiopians?

And if we go back to the belief that the inhabitants of these countries aren’t homogenous, they belong to different ethnicities. Then how do you know who is black and who is not? Is it the colour of their skin?

And if so, does it mean that if I have the skin colour of Angela Davis, I’m not black?

Identity is a two-way street. You can identify yourself in one way, and others would view you in another because you don’t fit the mould, just like Aaron (Tyriq Withers) from season three of Atlanta, a bi-racial high-school senior who failed to prove his blackness to win a full scholarship to college. Even Felix, the Nigerian young man, wasn’t admitted to the black club—until later when he was shot by the police—because, as a Nigerian, he could trace his ancestry and have a country and identity to fall back on.

Where do we go from here?

Suppose none of us can prove the purity of their African blood and their direct lineage to the ancient inhabitants of this land, why don’t we collectively celebrate our continent and the African diaspora and take pride in its great civilisations like Egyptian kingdoms, the kingdom of Kush, Aksum, Carthage, Yoruba, the Mali Empire, the Great Zimbabwe, the Ghana Empire, the Songhai Empire, the Harlem Renaissance, and so many others. And continue investing in African-led research and science to learn more about our ancestors, draw the line between facts and fiction, and unearth facts devoid of personal biases and racial supremacy. Some people don’t want to live a lie, even if the truth isn’t on their side.

Why don’t we build on the efforts of great Pan-African leaders like Nkrumah, Nyerere, Nasser, Sankara, Marcus Garvey, and others by investing in a collective African identity that encompasses all Africans on the continent and the diaspora that cuts across all shades and colours and ethnocultural identities, that fights the rising Afrophobia, racism, and colourism in North Africa and other parts of the continent? That embraces the complexity and intersectionality of identity.

About the author

Mirette Bahgat is an Egyptian creative writer based in Toronto. Her work has appeared in various publications, including Africa Risen, Ibua Journal, Ake Review, Afreada, HuffPost, and others. She was awarded The Toronto Arts Council creative writing grant in 2022, the American University Madalyn Lamont literary award in 2016 and the European Institute of the Mediterranean writing award in 2009. She was shortlisted for the Short Story Day Africa contest in 2016 and longlisted for the Nommo speculative fiction award in 2019. Mirette holds a postgraduate certificate in creative writing from Humber School for Writers and an MA in political science from the American University in Cairo.